%20(3)_optimized.jpg)

Trek into the Unknown

Chantal Onyango

Because his mother stumbled on her way home from the trickle, his name was derived from the cause of her condition: Mwanyigha. The one who dances.

Weighed down by water-filled clay pots, his poorly timed kick and a pirouette from within his mother’s belly threw her off balance. She grazed her shins badly enough to require an herbal poultice from the medicine woman and developed a limp for the remaining months of her turbulent pregnancy. Her left hip would never be the same as it once was.

Where others held grudges over the unborn for the suffering they caused, Mwanyigha’s mother attached no blame to her son. The very definition of her son’s name was a testament to her sense of humor. As is the intention with all tribal names, his name invoked his nature. It was reclaimed from disuse. A hand me down that purposely skipped a handful of generations before resurfacing when it sensed a cause for its return.

Names were odes to fate, whispered announcements of character before the child’s first words were spoken. It was cemented into being with the spilled blood of wild game. Polished as a wish of good fortune with yeasty mbangara 1poured liberally into drinking vessels. Attendees made sure to tip their cups; their libations darkened small patches of earth to quench the curious thirsts of ancestral spirits desperate for an affront of any kind to justify their re-entry into the land of the material.

All Mwanyigha had known was water. Its absence. Its abundance. Suspended in a watery embrace, his mother's uneven gait lulled him into deep sleep in his fetal state. After his screams filled his mother’s mud hut, he was introduced to the local stream when his mucky body was dunked into a stolen fraction of it, collected in an ornate clay basin. Shocked from the sudden emergence into an unmuted world, the warm bath soothed him. Months on, when his fragile neck could stand firm on its own accord, postponed chores required his mother’s attention. Mwanyigha tagged along to the stream with her every day. Wrapped in a sling made from softened hide. On the spongy banks carpeted with a bed of grass, the infant gurgled in competition with the moving water. Occasionally, his mother dipped him in up to the waist to cool his overheating body.

As he aged, Mwanyigha took to skimming pebbles downriver, taking pleasure in watching them bounce along for a couple of skips before they sought out a new home at the bed of the channel. Pre-teen years gave him the added responsibility of fetching water for his household for the want of siblings. Luckily, his uncle, Mwandware, helped him shoulder the burden whenever their paths crossed on his way home. His uncle became his confidant.

Much to his mother’s dismay, errant gossip reached her ears, passed on from her eavesdropping son. To the members of the Kichuku 2she had married into, she was not worth the cows paid to her father for her wupe 3. As long as Mwanyigha survived his father, her standing in the village’s hierarchy held fast. Mwanyigha planned to seize his birthright without incident.

Regular consultations with his forebears instilled the confidence he would need to lead his people. Voices from their place of rest beckoned him closer. They passed on their knowledge, playing their assigned roles as relics to a heritage they wished to direct to ascendency. Silent conference with Mulungu — the omnipresent deity from above — complemented his pilgrimage up to the summit of Wesu Rock.

Each lungful of air was a swallow of condensation. Tiny water droplets suspended in the atmosphere made it heavy. Mwanyigha swatted at the clouds to clear his blurry vision. As always, it was a futile activity. Instead, he relied on information gathered from prior trips to this lookout. He counted his steps as he neared the mossy edge. Fear sank hooks deep into his stomach. Tugged from all directions, his gut lurched from the sheer height of the tower. A single miscalculation spelled certain death.

Mwanyigha recalled a recent sentencing: a convict falling over the cliffside at an alarming pace, meeting his sentence on the rocks below. Proof that flesh has never been, nor would ever be, any match against millennia-old stone. The eyes of the onlooking crowd were spared from the explicit exhibition of mortality by the sack, woven from grasses, the convict was forced to wear.

Evidence of the thief’s existence was cleared away by the diligence of nature. Opportunistic predators made off with the bulk of the remains. Torrential rains washed away the aftermath of his crimes. Nothing was left behind to remember him by.

The executioner was left alone at the top of the giant outcrop. He would be the first to receive the maiden droplet when it fell, ensuring the lifeforce of his son, the last of his besmirched bloodline, truly vanished without a trace. It seeped into the ground, sucked down deep to a place that would prevent its revival.

Mwanyigha’s uncle, Mwandware, had been doomed to suffer the same fate. At the last minute, he had been saved by the influence of his brother, Mwanyigha’s father. Blessed with a second chance, he refused to take it for granted. He chose to sow his fortunes east of the expanse he grew up in. In spite of his freedom, Mwandware continued to bemoan the unjust accusations dealt against him. He did so only in the presence of Mwanyigha.

The implications of injustice were completely unfounded. The stolen produce, basketfuls of dried cowpeas as valuable as tangible currency, had indeed been found in his boma4, hidden half-heartedly under a pile of sleeping hides. Societal rules everyone else was bound by were ignored by an apathetic Mwandware.

Mwanyigha swore he wouldn’t follow either route: a shunned misfit banished to the dry, desolate wilderness or a common criminal without a legacy. The richness of the one he was born into stood to gain with his eventual addition to it. Of this, he was certain. He envisioned a more complete ending to his story. Death from old age or natural causes. There was a spot awaiting his arrival in the caves he passed on his way up to Wesu Rock.

Centuries old artifacts of his lineage glowed a brilliant white against the shadowed background of the cave. Frontal bones and outstanding cheekbones dusted with red soil; the honorable markings of time. With nearly two decades tucked into his elongated limbs, he prayed for five left over to fly by without trouble. Plenty of time for him to make his mark. His uncle’s travels east, baharini 5, fueled his ambitions.

The sun beamed from the direction where his dreams lay waiting for him. One day, long after his death, Mwanyigha’s skull would be one of the first to be kissed by the warmth of each new morning. Oriented towards the mouth of the cave. In the position of highest honor. Interred according to the rites passed down from generation to generation. Unchanged throughout the ages. He’d get there. He knew he would.

A plan was already set in motion. Mwanyigha made his way to the drop-off point; the birthplace of the idea that possessed him. According to his calculations, his aging father wouldn’t last much longer. After his passing, Mwanyigha would be free to usher in a new era. One of prosperity and discovery.

“Ndoni ya miaka ikumi6,” he murmured to himself.

Nawekabwa ni iruwa7

Mwanyigha imagined the state of his insides, taking inventory of the deterioration of his health since the trek began. The membrane of his throat would not have looked too dissimilar to the cracked surface his bare feet trod on, he reasoned. Spatterings of blood dotted his bare legs — courtesy of the low-hanging branches of wait-a-bit trees. Their proliferation was a lesson in survival, something Mwanyigha now needed to emulate.

Severe rungu 8blows against his temple emphasized the absence of water. Beneath his skin, the flurry of blood grew more furious. Vessels called to the surface by the sun overhead, as close to the dermis as they dared, lost their evolutionary efficiency in the torrid heat. Visual delusions activated by dehydration confused the senses he relied on. Optical illusions filled those who had no experience in this climate with despair. They were coaxed forward for sips of cool water at a tree-lined oasis promised at the end of the horizon, but the body of water spied by all fifteen pairs of eyes never came.

Onwards they trudged. Wildlife retracted their involvement whenever the caravan stumbled across a gathering. Bundles of tusks shone bright white against the tan backs of the camels. Herds of elephants silently grieved the remains of fallen compatriots. Gazes of understanding followed the human chain until they were out of sight. It was an undeserved sympathy. On his part, at least. Mwanyigha had been captured on his weekly diwa9 at the trade-off point where he stored a cache of dried-out game meat for his uncle to find. He expected a gift in return. An exotic wonder he never would’ve come across had he not maintained the tether between him and his prodigal relative. He used himself as a test subject, sacrificing himself for the betterment of the tribe. The marvels of the outside world would’ve been enough to convince them to dissolve their strict laws of isolation.

Mwanyigha’s source of shame could be found in a box. Hidden. Tucked in the boughs of a scraggly tree, unusual in its appearance. The birds who had graciously given up an abandoned nest for his precious treasure were sworn to secrecy. This was the one item he cherished most in this world.

He savored the salty dried fish. A complex flavor from an alien realm. Sinewy strips got caught in the narrow gaps of his teeth. His tongue relished the act of freeing them. He broke off a tiny piece of rolled bark. Heat and sweetness burst onto his taste buds as he chewed the pure spice. Before he returned home, he sat with a mouthful of ash to absorb the perfume of his illicit candy.

Lastly, he held up a small conch to his ear. The vast expanse of water mentioned by his uncle sang to him. Although he tried his hardest to visualize the white sand, the boundary line where the vault of the heavens sat on top of the impossibly blue water and the trees with elongated trunks that his uncle sketched into the rusty soil, his thoughts turned to vapor. Now he would get to see, smell, touch, and taste it all for himself. But not in the way he hoped.

Slavery was his restitution for taking more than was allowed from the land that already provided so much to them. His capture was a repercussion of his greed. The rules of nature gave no exceptions for human ambitions. Contact with his uncle’s corruption had infected him. Mwandware had given him up to his new people. They spoke the same tongue. Wore the same garb. Worshiped facing the same direction. Mwandware killed two birds with one stone: he appeased his new tribe by offering up his nephew and avenged the perceived besmirching of his name. Mwanyigha would pay the price for his blindness.

Pieces of the vivid descriptions passed on to him by his vagabond uncle oriented him. He could sense the caravan nearing their eventual destination. Along the way, the winding snake of a river found itself. No longer was it an emptied artery. A barren guide leading directly to the point of the journey’s end. It breathed again. At some point, the cracked soil turned to mud. The mud turned into a diluted slurry, and the slurry turned into a river once more. They squatted and sipped the murky water. Revival came from the return of the water. Browns turned to greens. The land exploded into high definition. Mwanyigha’s eyes were slow to adapt. By the time they adjusted themselves rightly in their sockets, an alternative problem arose to take the place of the former. A more sinister adversary stalked him as he was dragged forwards against his will.

Unbearable discomfort unwound the rope of his sanity. His connection to reality worn thin by the increasing transparency of the curtain. It started in the Kaya10. An extension of the damp mangrove environment into the terrestrial. An area of transition. A disputed boundary where power struggles erupted as the spirits on either side bled into the existential fields of their counterparts. Both factions required their own specific kinds of appeasement.

Mwanyigha watched the men, shrouded in white cotton now soiled from the efforts of their journey, lay offerings to carved figurines encircling the most dominant tree in the landscape. Where the fighi11 from his home territory gave him crisp and cold comfort, he was tormented by the invisible occupants of this forest and the conditions of the forest itself. Evil cackles followed him. Untraceable pokes and nudges provoked profound, unshakeable paranoia. All the while, he sweated profusely. He could no longer distinguish the difference between the salt in the air and the salt leaking out of his pores.

A conch shell was used as a ritualistic receptacle. Briny water was laid at the foot of the figurines. A plea for blessings over whatever negligible jurisdiction their ancestors covered in the ocean. Prayers for a safe passage were mumbled in monotonous droning. The words were left hanging in the air as the fifteen captives were led underground where the earth swallowed them whole.

Comfortable resting positions were unachievable. Their bound wrists were secured above their heads. Shackles on their ankles denied them the rein to stretch out their legs. Once the flames of torches carried by their captors were snuffed out around the bend of the passageway, a cloud of maisosi12 descended onto their restrained targets. Underneath the limestone ceilings, the captured slowly internalized their new reality.

Shrill cackles punctuated the gruesome recounts they shared with the prisoners during their short stay in Shimoni13. Their colorful illustrations painted pictures of horrors yet to come. A peculiar sense of enthusiasm was palpable in their delivery. They shrouded the fifteen. Sets of needle-sharp fangs sank into exposed necks when opportunities presented themselves.

Clangs of chains became a bargaining language. The sounds of metallic desperation pleaded with the earth itself for an escape. Their cries multiplied into echoes. No audible response spoke to the rocks’ impersonality. The aging structures owed nothing to the human cargo they sheltered.

Revitalized by their stolen meals, the bats could hardly keep still. Vibrating in anticipation. High-pitched screeching overrode the thumping of their own hearts beating when the time came to move the fifteen to the sailboat bobbing patiently in the shallows.

Mwanyigha’s breath hitched when he laid eyes on it for the first time.

Bahari.

Disbelief numbed him from the sensations of wading in waist-high water. They climbed the wooden ladder onto the deck of the boat where his calloused feet were tickled by the grain of the planks as he shuffled into the pen they would be crammed into for the duration of their passage.

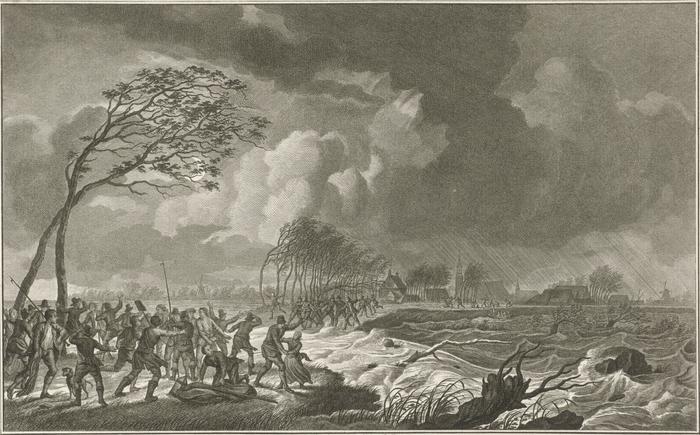

Steadiness was defined differently by a fisherman and land dweller. The rocking of the boat was a reminder of his name; he danced at the discretion of the incoming tide, stumbling on the wooden deck made from the trunks of centenarian trees. The currents of lakes, of rivers, could not compare. Lazy water is what he was used to. A bubble. A soporific gushing. A tentative sloshing at its most violent when all the rain funneled down the sides of the valley, the loud process of inundation still sounded like a lullaby to Mwanyigha’s ears. Here, far removed from everything he had ever known, the crashing of the waves felt menacing. Each slap against the hull was an ill omen.

Unnatural fog preceded them. Foul weather turned the peaceful tropical waters into a frenzied arena on the final day of their sail. Immovable obstacles without a place in the deep sea stood in their path. Tack after tack, they maneuvered their vessel through the minefield. It was time to present their sacrifice to placate the Nguva14. Oblivious to their significance, the happy coos of the caged birds were at odds with the emotions of everyone else aboard the dhow15. What could’ve been a comforting aroma—smoky wood heated in the sun, birds roasting on the contained coals, and the scent of freshly laundered sails—was quickly masked by the acrid stench of anxiety.

The slavers’ cheeks, swollen with packed leaves, chewed furiously. Potent stimulants dissolved by their saliva were swallowed. Periodically, they spat out the fibrous waste. Replacing them with fresh leaves. Pupils dilated. Hands busied themselves with imaginary tasks. Arguments arose and scarlet capillaries invaded the whites of their eyes. Was the trembling of their bodies a side effect of their drug habit? Or terror over the creatures who crawled up the hull of their boat, taking their rightful place at the bow?

Their stench was indescribable. Sharp teeth, gray and coated with green plaque, protruded from their oblong faces. Sunken, hunger- glazed eyes landed on the birds. The three Nguva present shared the birds amongst themselves. Stems of seaweed extended from the beds of their hair to fetch their snacks for them. Like limbs with fingers, they tore off charred chunks of meat and dropped them into their open mouths. When the last morsel was eaten, their dissatisfaction was shown by the darting of their beady eyes. The birds . . . they weren’t enough.

Unintelligible warbles muddled the air when they spoke. Like splashes of an underwater disturbance. Mischief lined their facial features. Human-like contours skewed from their usual proportions moved abnormally to address the leader. All eyes were fixated on them. The waters frothed with the Nguva’s displeasure. An arm reached out. Slender and double the length of a human being’s. A digit ending in a deadly point selected three of the fifteen. The lead slaver — without severing his ocular tie to the wild thing at the front of his boat — jerked his head to the left. One of his subordinates scurried into the dhow’s sole cabin. Emerging with a ring of keys. Tremors disrupted the function of his hands. The chosen three wailed their throats raw as the young man tried key after key on the shackle locks. The reason why they were chosen was obvious; all three of them had lots of muscle and fat left on their frames despite their 300 kilometer trudge through the bush. The first man was set loose and instinct took over. He leapt overboard. One of the Nguva grinned a ghastly smile before slinking back into the water in close pursuit. The other two sat still. Awaiting their inevitable end. The key bearer kicked them forward as Mwanyigha turned his head down. He shut his eyes and whispered a word of thanks over his lithe physique like a meditative mantra. His words blanketed the bloody screams, tempering them down to a fuzzy hum.

Bristles on wood scrubbing away the mess left in the Nguva’s wake brought Mwanyigha’s chant to a tapering halt. Blue skies and brilliant sunshine prevailed once more. The outline of a stone town built upon an island drew closer. Here is where Mwanyigha would slip through the cracks of history.

Zanzibar, The Spice Island.

Unenforced legislation made victims out of thousands. His eyes drank in the busy town where his trail, and his identity, would grow cold. Wafts of sweet cinnamon made him dizzy as they sailed into the harbor. A foreign smell sparked memories of home. Memories of the life he could never return to. In the end, his fate was worse than the two criminals he compared himself to.

Afterword

In Kenya, water and technology are inextricably intertwined. With the advent of our first undersea fiber optic cable, the floodgates of connectivity to the outside world burst open. The internet became readily available to a growing number of Kenyans, which brought about a steep increase in the usage of digital devices. Without this link, Mwanyigha’s story would not have existed.

The inspiration for this story was drawn from a National Geographic article I read in 2018, which focused on the creation of a digital archive of languages and dialects — Wikitongues — with added emphasis on the preservation of dying languages. At this stage, the idea of producing pieces to showcase the Taita culture — my tribal culture — was embryonic.

Years later, I found COMPOST’s call for pitches while surfing the web from the comforts of my living room. I was able to pull obscure information gathered by anthropologists, far more capable than I, from Google Arts & Culture at the click of a button. Recording phone applications was the backbone of my source gathering process. My grandfather, equipped with his first smartphone at the age of 87, recorded tidbits of relevant information which he sent over in bulk. The supernatural tales of the Nguva recounted to me by coastal fishermen were stored in the cloud for months, waiting for an opportunity to make themselves useful. Just like in Mwanyigha’s time, hundreds of years ago, integration to a broader network started way out at sea, as the first exploration boat sighted the Swahili coast on the horizon.

- Mbangara: An alcoholic drink made from sugar cane. ↩︎︎

- Kichuku: - Clan ↩︎︎

- Wupe: Dowry ↩︎︎

- Boma: Compound ↩︎︎

- Baharini: To/at the sea ↩︎︎

- Ndoni ya miaka ikumi: Less than ten years left ↩︎︎

- Nawekabwa ni iruwa: I am being beaten/hit by the sun ↩︎︎

- Rungu: A wooden hunting club ↩︎︎

- Diwa: Hunt ↩︎︎

- Kaya: Sacred forests of the Mijikenda people; the residence of ancestral spirits ↩︎︎

- Fighi: The Taita equivalent to the Kaya ↩︎︎

- Maisosi: Bats ↩︎︎

- Shimoni: The place of the hole ↩︎︎

- Nguva: Mermaids ↩︎︎

- Dhow: A single or double masted sailing vessel of Arab origin found in the western Indian Ocean, image courtesy of Alfajiri Dhow (@alfajiri_dhow) ↩︎︎

%20(3)_700x350.jpg)

_700x700.png)